Quick Overview of This Bible Study…

Short on time? I have created a short slide show presentation of some key takeaways in our study. The complete, more comprehensive bible study is below…

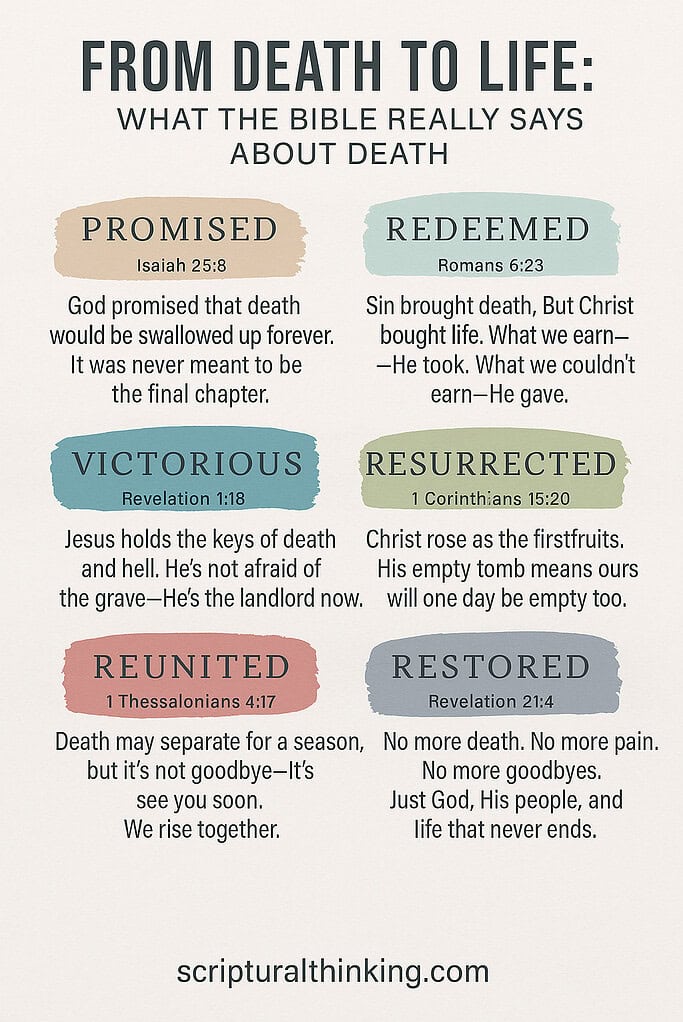

Death is one of life’s certainties, yet it often raises tough questions. How does the Bible talk about death?

In Scripture, death is not just a biological event but a profoundly spiritual concept. From the opening chapters of Genesis to the final scenes in Revelation, death is a recurring theme.

This deep Bible study will explore what physical death means, what spiritual death is, and how God’s Word weaves a redemptive story from death’s entrance to its ultimate defeat.

We’ll look at the original Hebrew and Greek terms for death, see how the Bible uses the word “death” in different ways, examine related concepts like Sheol and Hades, consider instructions for Christians on facing death, and revisit key biblical stories that illustrate death’s power – and God’s greater power of life.

The Meaning of Death: More Than the End of Life

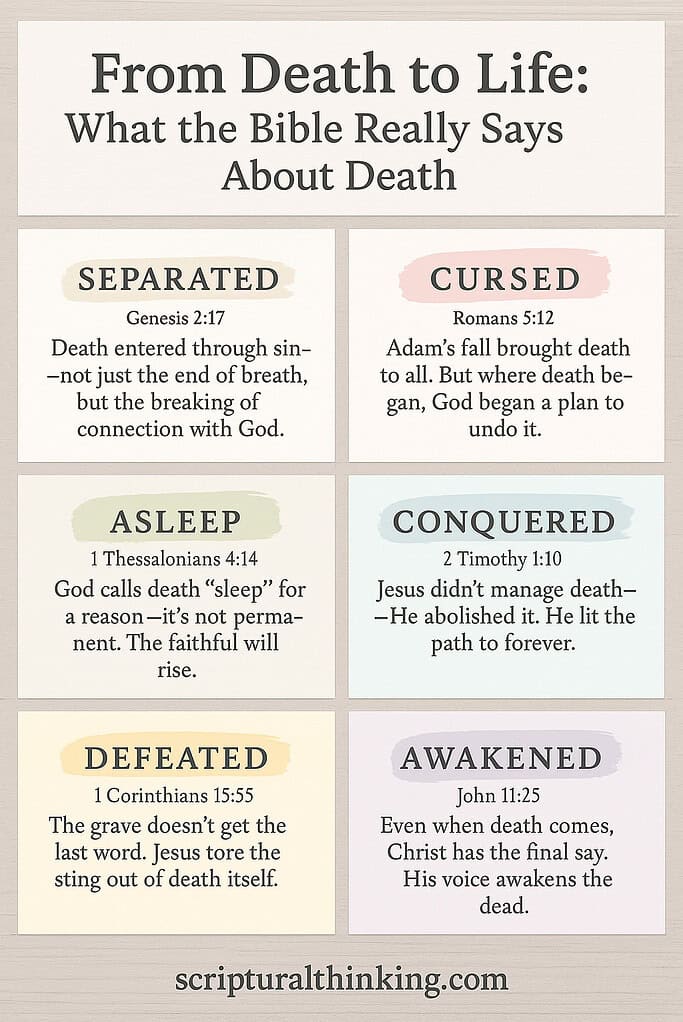

What exactly is death according to the Bible? At first glance, death might seem simply the cessation of life – when the heart stops beating and breath ceases. But biblically, there’s much more to it.

In Scripture, death fundamentally means separation – separation of the soul from the body in physical death, and separation of the soul from God in spiritual death.

This concept helps us understand why the Bible speaks of different “kinds” of death.

In the Old Testament

The main Hebrew word for death is māveṯ (מָוֶת). It literally means death or dying, but it can also refer to the state of death or even pestilence or destruction.

The term māveṯ is used both for physical death (the end of physical life) and as a symbol of spiritual death – the separation from God that sin causes.

- The Hebrew concept of death is tied to the Fall in Genesis: when Adam and Eve sinned, death entered creation. God had warned, “in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die” (Genesis 2:17, KJV).

Adam and Eve did not fall over dead physically the moment they ate the forbidden fruit, but something catastrophic happened – they were immediately alienated from God (spiritual death), and the process of mortality began in them (physical death to come).

- As Romans 5:12 (KJV) puts it, “by one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin; and so death passed upon all men.”

From that point on, every person inherits a world under the curse of death. The Old Testament reflects this reality: genealogies in Genesis punctuate each life with the refrain “and he died,” underscoring death’s universality.

In the New Testament

The Greek word for death is thanatos (θάνατος). Like its Hebrew counterpart, thanatos primarily means physical death but also encompasses spiritual death – separation from God because of sin – and even a final, eternal death as judgment.

The Bible teaches that a person can be “dead” spiritually even while physically alive (1 Timothy 5:6 speaks of a living person who is “dead while she liveth,” and Ephesians 2:1 says, “you... were dead in trespasses and sins,” referring to spiritual condition).

- Conversely, a person who has physically died can still be alive spiritually with God (Jesus said that the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, though long dead, are “alive unto God” – see Luke 20:37-38).

This shows that in Scripture, death is not extinction, but a separation.

Physical life and death refer to our earthly bodies, whereas spiritual life and death refer to our relationship with God.

It’s important to grasp this dual aspect of death because it’s at the heart of the Bible’s message.

Physical death is described in James 2:26 as the body without the spirit:

“For as the body without the spirit is dead…”. When we die physically, our soul/spirit is separated from our body – the material part returns to dust (Genesis 3:19) and the spirit returns to God who gave it (Ecclesiastes 12:7).

Spiritual death, on the other hand, is being alienated from the life of God.

This began with Adam and Eve’s sin, as they were cast out of Eden, away from God’s intimate presence. Isaiah 59:2 says, “your iniquities have separated between you and your God.”

In that sense, “the wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23) – not only do we eventually die physically because of sin, but sin also creates a spiritual death, a cut-off from the true life found in fellowship with our Creator.

The Bible even speaks of a “second death” (Revelation 20:14) – an ultimate form of death which is eternal separation from God.

This is linked to final judgment: those not redeemed by Christ face an eternity apart from God, described as the lake of fire (Revelation 21:8).

It’s a sobering concept: eternal death as the opposite of eternal life. But as we’ll see, God’s desire is to rescue us from this fate through Jesus Christ.

In summary, the meaning of death in the Bible goes beyond a tombstone. It carries theological depth – death is a consequence of sin, a curse intruding on God’s creation, a separation that needs healing.

But the story doesn’t end there, because the Bible is also the record of God’s plan to defeat death and restore life. Before we get to that victory, let’s break down the different ways the Bible talks about “death.”

Different Ways the Bible Uses the Word “Death”

Scripture uses “death” in more than one sense. To avoid confusion, here are the primary ways this word appears in the Bible:

Physical Death:

This is the most straightforward meaning – the end of physical life. It’s what we observe when someone’s body dies.

For example, “it is appointed unto men once to die” (Hebrews 9:27) refers to our mortal demise.

Almost every Bible character experiences this common fate (“and he died” is a constant refrain in Genesis 5).

Physical death is often spoken of in contrast to earthly life (e.g. Moses said, “I have set before thee this day life and good, and death and evil,” Deuteronomy 30:15).

It’s sometimes called the “first death” to distinguish it from other types.

Spiritual Death:

As discussed, this refers to a broken relationship with God – being alive in body but dead in spirit.

- When the prodigal son returned, the father says, “this my son was dead, and is alive again” (Luke 15:24), meaning he was spiritually lost and separated from the family, but now restored.

- Paul reminds Christians, “you hath He quickened (made alive), who were dead in trespasses and sins” (Ephesians 2:1, KJV).

A person spiritually dead lacks the connection to God’s life; they need salvation to be “born again” (John 3:3) into spiritual life.

Eternal Death (Second Death):

This phrase isn’t used in everyday conversation, but Revelation uses “the second death” for the final state of the wicked after judgment (Revelation 20:14, 21:8).

It’s essentially spiritual death made permanent – an everlasting separation from God’s presence.

Jesus alluded to this when He warned, “fear him which is able to destroy both soul and body in hell” (Matthew 10:28). The second death is what Christ came to save us from, by offering us eternal life instead.

Figurative Death to Sin/Self:

Interestingly, the Bible also uses “death” in a metaphorical way for the believer’s relationship to sin.

- For example, Romans 6:11 says, “reckon ye also yourselves to be dead indeed unto sin, but alive unto God through Jesus Christ.”

Here, “death” is positive – it means we are separated from the power of sin, as if our old sinful self died when Christ died.

- Paul even says, “I am crucified with Christ” (Galatians 2:20) and “I die daily” (1 Corinthians 15:31), expressing a continual choosing to deny self and live for God.

This figurative use highlights the transformative effect of salvation: our “old man” is put to death so that we can live a new life in Christ (Romans 6:4-6).

Personification of Death:

At times, “Death” is spoken of almost like a person or force.

- In 1 Corinthians 15:26, Paul writes, “The last enemy that shall be destroyed is death.” Death is depicted as an enemy of God and man.

- In Revelation 6:8, John sees a pale horse whose rider’s name was Death, symbolizing mass death or plague.

- And in Revelation 20:14, “Death and Hades” are thrown into the lake of fire – a vivid way to say they will be abolished.

This personification underlines that death is something hostile that will be defeated.

These various uses of “death” show why context in Bible reading is crucial. When you see the word death in a verse, ask: is this talking about physical death (like the end of someone’s life), spiritual death (like being lost in sin), or perhaps the second death (final judgment), or even a metaphor?

Often the context makes it clear. For instance, Romans 6:23 encapsulates two kinds in one sentence: “For the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

The “death” here is more than just physical (since all die physically, both sinners and saints) – it implies the spiritual and eternal death that sin brings, contrasted with eternal life that God gives. Understanding these nuances enriches our reading of Scripture on this subject.

Words and Concepts Associated with Death (Sheol, Hades, Grave, “Sleep”)

The Bible not only talks about death itself, but also uses various terms and imagery related to death. Some of these words might be unfamiliar or carry specific connotations in Scripture. Let’s look at a few key concepts closely associated with death:

Sheol (and Hades):

In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word Sheol is often used. Sheol is the realm of the dead, sometimes translated as “the grave” or “hell” in the KJV. It doesn’t specifically mean a place of torment (unlike our common use of “hell” today), but rather the shadowy abode of departed spirits.

- Everyone who died in the Old Testament era was spoken of as going to Sheol – the righteous and the wicked (Psalm 89:48, Ecclesiastes 9:10). It was essentially “the place of the dead” or the grave.

In the New Testament, the equivalent term is Hades, a Greek word used in the same way to mean the unseen world of the dead.

- For example, Acts 2:27 (KJV) quotes Psalm 16 regarding Jesus: “Thou wilt not leave my soul in hell (Hades), neither wilt thou suffer thine Holy One to see corruption.”

This was saying Jesus’ soul would not remain among the dead, nor His body in the grave, but that He would rise again.

- In Luke 16:22-23, Jesus tells a story involving Hades – the rich man’s soul goes to Hades after death and experiences torment, whereas Lazarus is comforted “in Abraham’s bosom.”

This suggests that Sheol/Hades had two experiences: rest for the godly and anguish for the ungodly, separated by “a great gulf” (Luke 16:26).

While interpretations vary, a common understanding is that before Christ’s resurrection, the souls of the righteous went to a pleasant side of Sheol (also called Paradise or Abraham’s bosom) and the wicked to a suffering side – all within the realm of the dead (Luke 16:25).

Sheol/Hades is a temporary state, because the Bible teaches there will be a resurrection.

- Ultimately, death and Hades will give up the dead (Revelation 20:13) and then be done away with (Revelation 20:14).

So, Sheol and Hades underscore the reality of an afterlife and interim state before the final judgment. They remind us that when someone dies, from an earthly perspective they “go to the grave,” but from a spiritual perspective their soul goes to an unseen realm awaiting resurrection.

“The Grave”:

The word grave in Scripture (Hebrew qeber or bor, Greek mnēmeion for a tomb) usually refers to the physical place where a body is laid. It can be a literal tomb, pit, or sepulcher. Yet “the grave” is also used poetically as a synonym for death itself.

- For example, in Job 17:13, Job laments, “the grave (Sheol) is mine house.”

- In 1 Corinthians 15:55, the KJV famously reads, “O grave, where is thy victory?” (where many other translations say “O death, where is your sting? O Hades, where is your victory?”).

The KJV there uses “grave” for Hades, highlighting how the grave is seen as the victory-holder when people die. But because of Christ’s resurrection, Paul taunts the grave – it will not have the last word!

- When you see references to “the dust of the earth” or “the pit,” those are often talking about the grave as well (for instance, Ecclesiastes 12:7 and Psalm 30:3).

The grave is essentially death’s domain in a physical sense – it’s where bodies go. However, the Bible repeatedly hints that the grave is not an irreversible prison.

- God’s power can reach even there (1 Samuel 2:6: “The LORD killeth, and maketh alive: he bringeth down to the grave, and bringeth up.”).

“Sleep” as a Metaphor for Death:

One of the most beautiful and frequent euphemisms the Bible uses for death is “sleep.” Especially for believers, Scripture often describes those who have died as having “fallen asleep.”

This doesn’t mean the soul is literally sleeping or unconscious (the idea of “soul sleep” is debated, but mainstream Christian thought teaches that the soul is conscious after death with the Lord – see Philippians 1:23, Revelation 6:9-10).

Rather, sleep is a metaphor that emphasizes the temporary nature of death for those who will be awakened in the resurrection. Just as a person who sleeps will wake up, so one who dies will rise again at God’s call.

This metaphor is found in both Old and New Testaments.

- In the Old Testament, Daniel 12:2 says, “many of them that sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake” – a clear reference to bodily resurrection.

- The phrase “slept with his fathers” is used repeatedly in Kings and Chronicles when a king died (e.g., 1 Kings 2:10: “David slept with his fathers, and was buried”).

- In the New Testament, Jesus uses this language. When His friend Lazarus died, He told the disciples, “Our friend Lazarus sleepeth; but I go, that I may awake him out of sleep” (John 11:11).

- The disciples misunderstood and Jesus had to clarify, “Lazarus is dead” (John 11:14).

Jesus wasn’t being coy; He was teaching a perspective. From His viewpoint, raising Lazarus was as easy as waking someone from sleep – and indeed, He did call Lazarus out of the tomb after four days.

- Similarly, when Jesus raised Jairus’s daughter, He said, “the maid is not dead, but sleepeth” (Luke 8:52), again showing that for Him, death is impermanent like sleep.

- The early Christians continued this usage. Stephen, the first martyr, after being stoned, “fell asleep” (Acts 7:60) – a gentle way to describe a brutal death, focusing on the hope that he will be awakened at Christ’s return.

Paul uses “sleep” for death multiple times, especially regarding believers who died before Christ’s second coming.

- 1 Thessalonians 4:13-14 is a key example: Paul writes so that believers “sorrow not, even as others which have no hope” concerning those who “are asleep,” and he assures that those who “sleep in Jesus” will God bring with Him, and that the dead in Christ will rise.

Referring to deceased Christians as “those who sleep in Jesus” shows the tender outlook the Bible encourages – yes, we still grieve the loss, but we see it as a sleep from which God will awaken them.

The metaphor also conveys rest. In death, one ceases from the labors and pains of this world (Revelation 14:13 says the dead who die in the Lord “rest from their labors”). Thus, “sleep” implies that death, for the believer, is like a restful sleep after a hard day’s work, with a bright morning to come.

Other Terms:

There are a few other words related to death worth noting briefly.

- Gehenna is a Greek term Jesus used for the place of final punishment (often translated “hell” in the NT). While not exactly “death” itself, it’s tied to the second death concept – the ultimate fate to avoid.

The word Gehenna comes from a burning garbage valley (the Valley of Hinnom) and signifies the permanent destruction of the wicked (see Matthew 10:28, 23:33).

- Another term, “the valley of the shadow of death,” appears in Psalm 23:4 – “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil.”

This phrase paints a poetic image of life’s most perilous and dark experiences (including literal danger of death), yet the believer fears no evil because God is present even there.

- And finally, Abaddon (Hebrew for “destruction”) or Apollyon (Greek for “Destroyer”) is mentioned in Revelation 9:11 as the name of an angel of the bottomless pit, but in the Old Testament “Abaddon” can be a poetic name for the realm of the dead or destruction (Job 26:6, Proverbs 15:11).

These terms contribute to the Bible’s rich vocabulary on death and the afterlife.

To sum up, when reading the Bible’s references to Sheol, Hades, the grave, or sleep, it helps to remember:

- Sheol/Hades is the unseen realm of the dead (the “grave” in a general sense)

- the grave is where the body goes (often used synonymously with death)

- “sleep” is a kind metaphor for death, especially of believers, implying rest and eventual awakening.

All these concepts reinforce that, from the Bible’s perspective, death is real but not final – it’s a state from which God can and will awaken His people.

Instructions to Christians on Death: Facing It with Faith, Not Fear

Death is a stark reality, but the Bible gives clear guidance on how Christians are to understand and respond to it. One remarkable thing about the New Testament is how it transforms the outlook on death in light of Jesus Christ. Here are some key instructions and principles for believers regarding death:

Do Not Fear Death (Christ Has Conquered It):

The single most repeated command in Scripture is “fear not.” When it comes to death, the Bible explicitly encourages believers not to live in fear of it.

Hebrews 2:14-15 tells us that Jesus became human so that “through death he might destroy him that had the power of death, that is, the devil; and deliver them who through fear of death were all their lifetime subject to bondage.”

Jesus’ death and resurrection broke the power of death and the devil, freeing us from slavery to the fear of dying. This doesn’t mean we court death or enjoy the idea of dying, but it means we no longer have to be terrified of what’s beyond it.

- 2 Timothy 1:10 triumphantly says our Savior Christ “hath abolished death, and hath brought life and immortality to light through the gospel.”

For the Christian, death is a defeated foe.

- As Paul proclaimed, “O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?… Thanks be to God, which giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Corinthians 15:55-57, KJV).

Because Jesus rose from the dead, those who belong to Him have the assurance that death will not have the final say. This assurance greatly reduces the fear factor.

The sting of death (its power to harm) was sin and judgment, but Christ bore our sins and took our judgment, removing the sting.

View Death as Gain (Being with Christ):

Christian teaching radically reframes death as, paradoxically, something “better” in certain respects.

- The Apostle Paul, while imprisoned and unsure if he might be executed, wrote about his internal debate: “For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain” (Philippians 1:21).

How could dying be gain?

- He explains a few verses later: “to depart, and to be with Christ; which is far better” (Philippians 1:23).

Paul wasn’t suicidal nor dismissive of life – he was passionately living for Christ – but he knew that being at home with the Lord (2 Corinthians 5:8) would be even greater.

This perspective is instructive: for a Christian, death is not loss of life but gain of closer presence with Jesus. It’s like graduating to a fuller existence.

- However, Paul also notes that living on in the flesh meant fruitful labor and was more needful for the church (Phil. 1:22-24).

So Christians hold a balanced view: we don’t seek death (we have meaningful work to do here), but neither do we dread it, because it brings us into the direct presence of the Lord, which we desire.

- In 2 Corinthians 5:6-8, he says we are confident and even willing rather “to be absent from the body, and to be present with the Lord.”

This teaches us that at the moment of a believer’s physical death, though they are absent from the body (which goes to the grave), their soul is immediately present with Jesus. That is a comforting certainty.

Grieve with Hope, Not Despair:

- Christians still feel the pain of loss when a loved one dies – even Jesus wept at Lazarus’s tomb, showing it’s normal to mourn (John 11:35).

- Yet, we are told not to grieve “as others which have no hope” (1 Thessalonians 4:13).

- We do grieve, but differently. Because we believe in the resurrection, our grief is tempered with hope.

- We know that for those who die in Christ, it’s a temporary separation.

- We have the promise of reunion when Christ returns and the dead in Christ rise.

In the meantime, we take comfort that our loved ones who knew the Lord are safely in His presence. The Scripture calls this hope “an anchor of the soul” (Hebrews 6:19).

So, at Christian funerals, there is sorrow, yes, but also often an undercurrent of joy and celebration of the person’s homegoing.

The Bible even says, “Precious in the sight of the LORD is the death of his saints” (Psalm 116:15), meaning God cares deeply about and welcomes the death of His faithful ones – not that He delights in death, but He delights in bringing His children home to Himself at the end of their earthly race.

Live in Light of Eternity:

Knowing that our time on earth is limited and that eternity is ahead should motivate a Christian to live purposefully.

- Psalm 90:12 prays, “So teach us to number our days, that we may apply our hearts unto wisdom.” We’re encouraged to make the most of our earthly life for God’s glory, because we won’t get a redo after death on what we did here.

- Ephesians 5:15-16 urges us to walk wisely, “redeeming the time.” Also, we are to be prepared – not in an anxious way, but in a faithful way – to meet the Lord at any time.

- Jesus often taught parables about being ready (like the wise and foolish virgins in Matthew 25:1-13) which, while about His return, also apply to the unpredictability of life’s end.

- “It is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment” (Hebrews 9:27).

Since death is an appointment we all will keep (unless Christ comes first), we should trust in Christ now and live each day in His grace.

For the believer, judgment is not about condemnation for sin (Christ took care of that) but about giving account of our lives and receiving rewards (2 Corinthians 5:10). That perspective helps us prioritize what really matters.

Be Faithful Unto Death:

In Revelation 2:10, Jesus tells the church, “be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life.” Christians are encouraged to persevere in faith even if it leads to physical death (as it did for many martyrs).

We see examples like Stephen in Acts 7, who faced death with forgiveness on his lips, or the Apostle Paul, who said he was ready not only to be bound but to die for Jesus’ name (Acts 21:13).

The grace God gives is sufficient to carry His people even through the valley of death. A crown of life – eternal life’s victor’s wreath – awaits those who hold fast. This instills courage: physical death for Christ is not defeat but ultimate victory.

Comfort and Encourage One Another:

The Bible also instructs Christians to encourage each other with the hope we have.

After describing the coming resurrection and rapture of believers in 1 Thessalonians 4:13-17, Paul says, “Wherefore comfort one another with these words” (1 Thess. 4:18).

We’re meant to remind each other of the promises of God regarding life after death. In times of illness or approaching death, Christians can gently encourage the dying person (if they’re a believer) that they are about to be with the Lord, free from pain.

We can comfort the bereaved by sharing Scripture about the resurrection and eternal life. This mutual encouragement is a way we bear each other’s burdens.

In essence, the Christian attitude toward death is marked by peace, hope, and even joy, because Jesus has changed what death means. As Dr. Terry Ellis put it, the Bible is a record of God’s effort to defeat death – the great enemy – and restore life.

When Jesus stood outside Lazarus’s tomb, He wept (John 11:35). He didn’t dismiss death’s sorrow; He entered it. But then He proceeded to call Lazarus out from death, demonstrating His authority.

Finally, Jesus went to the cross to grapple with death Himself. In doing so, He took the sting of death for us. The result is captured in 2 Timothy 1:10 – our Savior “hath abolished death.”

For the believer, then, death is more like a door than a brick wall – a passage into the nearer presence of God. We approach it solemnly yet confidently, sorrowfully yet hopefully, and always with the assurance that “the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

Death in the Old Testament: Key Examples and Foreshadowings

Throughout the Old Testament, we find numerous narratives and teachings that involve death – sometimes in very dramatic ways.

These stories serve to illustrate the reality of death in a fallen world, but many of them also foreshadow God’s power to overcome death or point ahead to the need for a Savior. Let’s survey some significant Old Testament moments related to physical and spiritual death:

The First Death and the Fall (Genesis 3-4):

Death makes its entrance early in the Bible. In Genesis 3, after Adam and Eve sin, God pronounces the consequences: “dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return” (Gen. 3:19).

They were expelled from Eden, and notably, prevented from eating from the Tree of Life lest they live forever in a fallen state (Gen. 3:22-24).

This sets the stage: humanity is now mortal. The very next chapter records the first human death – and it’s a murder. Cain kills his righteous brother Abel (Gen. 4:8).

Abel becomes the first person to physically die, and his blood cries out from the ground. This tragedy shows sin’s ugly fruit (jealousy leading to violence) and introduces the pain of bereavement.

Adam and Eve literally lost a son to death. By the end of Genesis 5, the refrain “and he died” tolls like a funeral bell for each descendant of Adam, emphasizing that God’s word “thou shalt surely die” came to pass.

Yet, even here, there is a glimmer of hope: in Genesis 5:24, one man, Enoch, “walked with God: and he was not; for God took him.” Enoch did not see death – God took him directly.

It’s a tiny foretaste that God has power over death and that intimate fellowship with God is the way to life. (Elijah later would have a similar story in 2 Kings 2:11, taken up to heaven in a whirlwind, bypassing death.)

The Flood and Divine Judgment (Genesis 6-9):

In Noah’s story, death comes as a judgment on a world utterly corrupted by violence and evil. The Flood causes the widespread death of humanity (save Noah’s family) and animals, a sobering demonstration that “the soul that sinneth, it shall die” in a collective sense.

Yet, through the ark, God preserves life to start anew. After the Flood, God makes a covenant and one of the promises is that He will never again destroy all flesh with a flood (Gen. 9:11).

The Flood narrative reinforces both the seriousness of sin (leading to death) and the mercy of God in providing a means of salvation (the ark foreshadows salvation from judgment).

Sacrifices and the Passover: Death as Substitution:

A strong theme in the OT is sacrifice, which by definition involves death – typically the death of an animal. When Adam and Eve sinned, God clothed them with skins (Gen. 3:21), implying an animal’s life was taken to cover their shame. This is the first hint of sacrificial death.

In Exodus, on the first Passover night, each Israelite household had to kill a spotless lamb and put its blood on the doorposts. Death visited Egypt’s firstborn sons, but the homes marked by the lamb’s blood were passed over (Exodus 12:12-13).

The lamb died in place of the firstborn. This idea of an innocent life given so that others might be spared is a huge foreshadowing of Christ (whom the New Testament calls “our Passover” in 1 Cor. 5:7).

The yearly Passover ritual would remind Israel that a death had occurred so they could go free. Similarly, the entire Levitical sacrificial system (laid out in Leviticus) taught that the wages of sin is death, but God allowed a substitute (a bull, goat, lamb, etc.) to die in the sinner’s stead.

Day after day, year after year, rivers of blood flowed at the tabernacle and later the temple – a constant visual aid that sin brings death, yet through a God-ordained sacrifice, atonement (covering) could be made.

None of those animal sacrifices could truly take away sin (Hebrews 10:4), but they pointed forward to a perfect Sacrifice to come.

Isaiah 53, an Old Testament prophecy, speaks of a suffering servant who would be “wounded for our transgressions” and “his soul” made “an offering for sin,” bearing the iniquities of others and pouring out his soul unto death – a clear prophecy of Christ’s atoning death to come.

Stories of Faith and Resurrection Hopes:

We also see individuals in the Old Testament exhibiting faith in God’s power over death. A standout example is Abraham. In Genesis 22, God tested Abraham by asking him to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. This was a heart-wrenching command – Isaac was the child of promise, and human sacrifice was not God’s way.

Yet Abraham obeyed, trusting God’s goodness. The Book of Hebrews sheds light on Abraham’s mindset: Abraham believed that if Isaac died, God was able to raise him up, even from the dead (Hebrews 11:19).

In a sense, Abraham did receive Isaac back from death, because at the last moment God stopped the sacrifice and provided a ram instead.

Isaac’s near-death and restoration on the “third day” of their journey (Gen. 22:4) is a powerful type of Christ – it foreshadows God the Father offering His only Son on the cross and receiving Him back in resurrection.

We can imagine the joy of Abraham as Isaac walked back down that mountain alive – a small picture of the joy of resurrection.

Other hints of resurrection hope appear: Job, in the midst of his suffering, declares faith that even after worms destroy his body, “yet in my flesh shall I see God” (Job 19:25-27) – a remarkable statement of belief in a bodily resurrection and Redeemer.

The prophet Ezekiel in chapter 37 has a vision of a valley of dry bones which, at God’s command, come back to life, covered in flesh and breathing again. While this vision symbolized the restoration of Israel from exile (spiritual revival of the nation), the imagery is resurrection.

It shows that God can make very dry bones live. Similarly, Isaiah 26:19 proclaims, “thy dead men shall live, together with my dead body shall they arise.”

These verses indicate that the idea of God raising the dead was not absent in the Old Testament – it was a “developing concept,” becoming clearer as time went on.

God’s Power Displayed over Death:

On a few occasions, God literally raised someone from the dead in the Old Testament, giving a preview of His resurrection power. Elijah the prophet raised a widow’s son in 1 Kings 17:17-24 – the first recorded resurrection in the Bible.

Later, Elisha (Elijah’s successor) raised the Shunammite woman’s son (2 Kings 4:32-37). And in a strange miracle even after Elisha died, a dead man was thrown into Elisha’s tomb and when his body touched Elisha’s bones, the man came back to life (2 Kings 13:20-21)!

Each of these instances was a gracious act of God to show mercy and also to authenticate His prophets. They also shout to us: The God of Israel has power to reverse death! This sets the expectation that God ultimately can conquer death.

Death as a Punishment or Consequence:

Many OT narratives illustrate death as the consequence of sin in a direct way.

For example, during the wilderness journey, when Israel rebelled or grievously sinned, death often followed – whether it was the ground opening to swallow Korah and his followers (Numbers 16:30-33) or a plague striking the people after worshipping the golden calf (Exodus 32:35).

The entire generation that disbelieved God at Kadesh-barnea died in the wilderness (Hebrews 3:17-19).

These sobering stories underscore God’s holiness and the truth that sin leads to death.

On the other hand, there were also cities of refuge established (Numbers 35) to protect someone who caused accidental death – showing God’s value of due process and mercy even in matters of life and death.

In all these examples, the Old Testament is painting two complementary truths: death is a terrible reality because of sin, and God has the power and intention to overcome it.

The stage is set for a Messiah who would “swallow up death in victory” (Isaiah 25:8) – a direct quote from Isaiah that the New Testament later applies to Jesus’ triumph (1 Corinthians 15:54).

The Old Testament ends with people still dying (even Moses died and was buried), but expectations of resurrection and eternal life were percolating.

By the time of Jesus, many Jews (like the Pharisees) firmly believed in a coming resurrection of the dead “at the last day” (John 11:24). God’s progressive revelation through the OT laid the foundation for what would happen when Christ came.

Death in the New Testament: Christ’s Victory and Our Hope

When we turn to the New Testament, we enter the climactic chapter of the story of death. Here, the Son of God steps directly into our mortal world, experiences death Himself, and rises again.

As a result, the entire tone of the Bible’s message about death shifts from long-held expectation to glorious fulfillment. Key examples and teachings in the New Testament center around Jesus Christ – His power over death, His own death and resurrection, and what that means for us. Let’s highlight some of these:

Jesus’ Power Over Physical Death:

During His ministry, Jesus demonstrated repeatedly that He had authority even over death. The Gospels record three dramatic resurrections Jesus performed (aside from His own).

- He raised Jairus’s daughter, a 12-year-old girl who had just died, saying, “Maid, arise” – and she came back to life (Luke 8:52-55).

- He stopped a funeral procession in Nain to raise a widow’s only son, simply telling the young man, “Arise” (Luke 7:11-15).

- And most famously, Jesus called Lazarus out of the tomb after Lazarus had been dead four days (John 11:1-44).

In each case, the people were truly, certifiably dead – and Jesus returned them to life with a word of command.

These miracles show Jesus as the Lord of life. They also deeply moved those who witnessed them (when Jesus raised Lazarus, many believed on Him – John 11:45).

Importantly, each of these individuals eventually died again later (their resurrections were temporary restorations). But they served as signs pointing to Jesus’ identity as the Resurrection and the Life (John 11:25).

The Death and Resurrection of Jesus:

This is the heart of the Christian faith. Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection are the most significant events in the Bible’s treatment of death.

- On the cross, the immortal Son of God willingly tasted death for every man (Hebrews 2:9).

- It’s almost unthinkable: the Creator of life died. He cried out, “It is finished,” gave up His spirit, and was buried (John 19:30, 19:40-42).

For His followers, it was the darkest moment – the Light of the world had been extinguished, or so it seemed. But this was all according to God’s redemptive plan, foretold by the prophets.

Jesus had said repeatedly that He would be killed and on the third day rise again (Mark 8:31, etc.), though even His disciples didn’t grasp it at first.

Then Easter morning came. Jesus rose bodily from the grave, leaving behind an empty tomb.

- The women who came to anoint His body were greeted by angels who said, “Why seek ye the living among the dead? He is not here, but is risen” (Luke 24:5-6).

- The resurrection of Christ is presented in the New Testament as the ultimate game-changer: “Christ is risen from the dead, and become the firstfruits of them that slept” (1 Corinthians 15:20).

The term “firstfruits” implies a larger harvest to come – His rising guarantees the resurrection of all who belong to Him.

Romans 6:9 declares, “Christ being raised from the dead dieth no more; death hath no more dominion over him.” Unlike the people Jesus raised during His ministry, Jesus rose never to die again – He conquered death permanently.

Through His death and resurrection, Jesus defeated death on our behalf.

- 2 Timothy 1:10 (as mentioned earlier) says Jesus “abolished death.” Hebrews 2:14 says He destroyed the devil’s power of death.

It’s as if Christ went into death’s domain (Hades/Sheol) and broke out, shattering the chains from the inside.

- Revelation 1:18 records Jesus’ words, “I am he that liveth, and was dead; and, behold, I am alive for evermore, Amen; and have the keys of hell and of death.”

In ancient times, possessing “the keys” signified authority. Jesus holds the keys of death and Hades now – He’s in charge of who lives and who dies and who will be raised. This is immensely comforting for believers: our Lord holds the keys.

The New Testament writers exult in Jesus’ resurrection as the guarantee of our own.

“Because I live, ye shall live also,” Jesus promised (John 14:19).

- Romans 8:11 adds that the Spirit who raised Jesus will also give life to our mortal bodies. Death could not keep Jesus, and it will not ultimately keep us either.

Salvation Described in Terms of Life and Death:

The New Testament often frames the gospel as a matter of being brought from death to life. Conversion is like a resurrection.

- Ephesians 2:4-5 says, “But God, who is rich in mercy… even when we were dead in sins, hath quickened us together with Christ (by grace ye are saved).” “Quickened” in KJV means “made alive.”

To be saved is to partake in Jesus’ resurrection life even now in our inner being.

- Colossians 2:13 similarly: “And you, being dead in your sins… hath he quickened together with him, having forgiven you all trespasses.”

Baptism is the outward symbol of this truth – Romans 6:3-5 explains that when a believer is baptized, it is a picture of being buried with Christ into death and then raised to walk in newness of life.

It’s identification with Jesus’ death and resurrection. Every baptism is a little dramatization of what happened to us spiritually and what will happen to us physically: we go under the water (a “grave” symbol), then come up (symbolizing resurrection).

So, the New Testament uses death and life in a spiritualized way to teach that through faith, we die to our old self and are born again to eternal life.

The Promise of Our Resurrection and Eternal Life:

Christ’s resurrection is the first part of the divine plan to ultimately eliminate death for His people. The New Testament is full of promises about the future resurrection of believers.

- 1 Corinthians 15 is a whole chapter Paul devotes to resurrection. He explains that when Christ returns, “the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed” (15:52).

- Our perishable bodies will be transformed into imperishable, immortal bodies suited for eternity – “this mortal must put on immortality” (15:53).

- Then will come to pass the saying, “Death is swallowed up in victory” (15:54, quoting Isaiah 25:8).

It’s a thrilling climax: death, the long-time enemy, will be swallowed, gone forever.

- Revelation 21:4 gives a beautiful glimpse of our future hope: in the New Heaven and New Earth, God “shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain.”

Imagine – a world where death is a distant memory, a vanquished foe. That’s the destiny for God’s children. Meanwhile, the New Testament also teaches the concept of the “second death” for those who reject God.

- Revelation 20:14-15 and 21:8 specify that those not in the Lamb’s Book of Life will face the second death – the lake of fire. But it’s clearly stated that “he that overcometh shall not be hurt of the second death” (Revelation 2:11).

- To “overcome” in John’s writings means to conquer through faith in Jesus (1 John 5:4-5).

So believers will never experience that ultimate death. Our worst case is physical death, and even that will be undone by resurrection.

- Luke 20:36 says that in the resurrection, we can no longer die but are like angels, immortal.

Martyrdom and the Church’s Witness:

- The New Testament church initially faced intense persecution, and many believers were killed for their faith (Stephen in Acts 7, James in Acts 12, Antipas in Rev. 2:13, and countless others in later history).

What’s striking is the courage and hope with which they faced death. This boldness came from their absolute certainty that death was not the end.

- Stephen, while being stoned, looked up and saw Jesus standing at God’s right hand, and said “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit” (Acts 7:59-60).

He died more concerned about his executors (“Lord, lay not this sin to their charge”) than about himself.

- The Apostle Paul, who stared death in the face many times, could say “Ourselves also, which have the firstfruits of the Spirit… groan within ourselves, waiting for…the redemption of our body” (Romans 8:23).

Early Christians were even known to sing hymns in their martyrdom, viewing it as departing to be with Christ.

- The Book of Revelation depicts martyrs as overcomers who “loved not their lives unto the death” (Rev. 12:11) – their eyes were on the eternal reward.

The spread of the Gospel in the early centuries was fueled in part by unbelievers seeing that Christians did not fear death like others did; as one church father said, “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.”

Practical Comfort:

The New Testament also provides tender moments of comfort regarding those who have died.

- A notable example is when Jesus comforts Martha in John 11. Martha said she knew her brother Lazarus would “rise again in the resurrection at the last day.”

Jesus responded with one of the most powerful revelations: “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. Believest thou this?” (John 11:25-26).

In one statement, Jesus affirmed the future resurrection (Lazarus will live again) and also declared that those who believe in Him have a life that transcends physical death (they “shall never die” in an ultimate sense).

We often read this at Christian funerals because it’s the crux of our hope.

- Another comforting passage is 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18 (already referenced), where Paul assures believers that the dead in Christ will rise and we will meet them again when Christ returns, therefore “comfort one another.”

The New Testament doesn’t ignore the sadness of death (it calls death an enemy, after all), but it consistently reframes it in the light of Christ’s empty tomb. For every tear, it offers a promise.

In the New Testament, death is effectively dethroned.

It is still an enemy, but a defeated one, with its doom sealed.

- The early Christians preached Jesus’ resurrection as the ultimate good news that “God hath given to us eternal life, and this life is in his Son” (1 John 5:11).

Eternal life, in their understanding, doesn’t mean merely living forever (everyone’s soul is immortal in that sense, either in heaven or hell), but a quality of life – living forever in the joyous presence of God, with death and sin gone.

- John 5:24 records Jesus saying, “He that heareth my word, and believeth on him that sent me, hath everlasting life, and shall not come into condemnation; but is passed from death unto life.”

Notice the past tense: hath (has) everlasting life already, and is passed from death to life. There’s an immediate spiritual new life when one believes, and a future physical new life promised.

- Death for a believer becomes like a shadow they walk through (Psalm 23) or a sleep from which they wake, rather than a pit from which they can’t escape.

The apostolic message is clear: Jesus lives, and because He lives, we who trust Him will live also. Thus, they urge us to hold fast to this hope, encourage one another, and keep perspective.

Paul’s rhetorical question in Romans 8:35,38 brings it home: “Who shall separate us from the love of Christ? … For I am persuaded that neither death, nor life… shall be able to separate us from the love of God, which is in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Even death cannot sever the relationship between the believer and Christ – in fact, it brings us into His immediate presence. Truly, “to die is gain.”

Symbolism and Metaphors of Death in Scripture

The Bible is rich in imagery, and it often uses symbolism and metaphor to communicate truths about death – sometimes to soften it, sometimes to explain its effect, and sometimes to show its defeat.

We’ve already discussed one major metaphor: death as “sleep.” Let’s consider a few other symbols and metaphors involving death in the Bible:

The Valley of the Shadow of Death:

- In Psalm 23:4, David uses this poetic phrase as he writes, “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for Thou art with me.”

This “shadow of death” evokes the darkest, most perilous experience one can face – as if death is a great shadow casting darkness over the valley.

The beautiful part is that even there, God’s presence dispels fear. The metaphor reminds us that for God’s people, death is like a shadow – it may scare us, but a shadow implies the presence of light on the other side.

A shadow can’t exist without light somewhere! Moreover, a shadow is not the substance itself. This suggests that for the believer, death’s substance has been removed (Christ took the “sting”), and what remains is just a shadow.

We also note the word “through” – we walk through the valley, we don’t stay in it. It’s a passage, not a destination.

So Psalm 23 offers a comforting metaphor: death is a valley we traverse with God as our shepherd, and beyond it lies the house of the Lord where we will dwell forever (Psalm 23:6).

Cup/Baptism as Symbols of Death:

Jesus at times referred to His impending death using symbolic language like a “cup” or a “baptism.”

- In the Garden of Gethsemane, facing the cross, He prayed, “O my Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me: nevertheless not as I will, but as thou wilt” (Matthew 26:39).

The “cup” was a common Old Testament metaphor for experiencing something to the full, often God’s wrath or judgment (Psalm 75:8, Isaiah 51:17). By calling His death “this cup,” Jesus signified that He was about to drink the full measure of suffering and the wrath of God for sin on our behalf.

Similarly, in Mark 10:38, He asks James and John, “Can ye drink of the cup that I drink of? and be baptized with the baptism that I am baptized with?” Here, He uses baptism as a metaphor for being overwhelmed or immersed in suffering (Luke 12:50, He says, “I have a baptism to be baptized with; and how am I straitened till it be accomplished!”).

Both these metaphors – cup and baptism – highlight the depth of Christ’s suffering in death. They are images of Him fully entering into death’s experience for us.

They also convey that His death was something He consciously submitted to (He drank the cup willingly, He stepped into the “waters” of suffering voluntarily).

The Cross:

The cross was an actual instrument of execution, but it has become a powerful symbol in Scripture for self-denial and identification with Christ’s death.

- Jesus told His followers, “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me” (Luke 9:23).

In that culture, the cross meant one thing: a one-way journey to death – carrying your cross meant you were a condemned man walking to execution.

So Jesus is saying that being His disciple involves a kind of death to self every day – a willingness to crucify our own desires in order to obey God.

- Paul picks up this metaphor when he says, “Our old man is crucified with Him” (Romans 6:6) and “I am crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but Christ liveth in me” (Galatians 2:20).

Of course, Christians aren’t literally nailed to crosses; this is symbolic language. But it powerfully conveys the idea of dying to an old life and living a new one by Christ’s power.

The cross, once a symbol of shame and death, becomes for believers a symbol of salvation, commitment, and new life through death.

- It’s why Paul says he would boast in “the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world” (Gal. 6:14).

The world had effectively become dead to Paul, and he to it – its charms no longer controlled him – because of the transformative power of Christ’s cross.

Seed Falling into the Ground:

Jesus used an agricultural metaphor to explain the purpose of His death.

In John 12:24, as He anticipated the cross, He said, “Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.”

Here the seed represents Himself (and by extension, any of His followers who would “lose their life” for His sake).

Just as a seed has to be buried in soil and essentially die as a seed to produce a plant and many new seeds, so Jesus’ death would produce a vast harvest of new life – the salvation of many.

This metaphor shows the paradox that life comes through death. It also applies to us in a principle: sometimes we have to “die” to our own plans or go through “death-like” sacrifices in order for God to bring rich fruit from our lives.

Sting of Death:

- In 1 Corinthians 15:55-56 (as mentioned), Paul personifies death and speaks of its “sting.” “The sting of death is sin; and the strength of sin is the law.”

This metaphor pictures death like a venomous bee or scorpion. The sting that makes death so painful and poisonous is sin, because sin is what brings judgment. The law (God’s holy standard) gives sin its strength because the law, when broken, justly condemns.

But the very next verse shouts, “Thanks be to God, who giveth us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.” Jesus removed the sting by forgiving our sins and satisfying the law’s demands.

Imagine a bee’s stinger stuck in someone – once a bee stings, it leaves the stinger and can sting no more. Christ, in a sense, allowed Himself to be stung by death – and the sting (sin’s penalty) stayed in Him.

He bore our sins on the cross, taking the venom, so to speak. Now death approaches a Christian like a bee with no stinger – it might buzz and scare, but it cannot inflict eternal harm. This is a triumphant metaphor of death’s disarmament.

Birth Pangs:

Interestingly, the New Testament also uses the imagery of childbirth in relation to death and resurrection.

- Jesus in John 16:21 compares the sorrow His disciples would feel at His death to a woman in labor – intense pain, but then joy when the child is born.

That metaphor extends to the idea that the sufferings of this present time (including death) are like labor pains leading to the birth of the new creation. Romans 8:22-23 says the whole creation groans and travails in pain, waiting for the resurrection (the redemption of our bodies).

In that sense, the agony of death is like the final contraction before the new life of resurrection bursts forth. It’s a hopeful metaphor because it frames death not as simply an end, but as an anticipation of something glorious about to emerge – just as a mother endures pain knowing it results in the joy of a new baby.

Garments of Mortality:

Another metaphor Paul uses for death and resurrection is that of taking off and putting on clothing.

- In 2 Corinthians 5:1-4, he speaks of our earthly body as a tent that will be taken down, and we have a heavenly building from God. He says we groan, desiring not to be “unclothed” (without a body) but to be “clothed upon” with our heavenly body, so that “mortality might be swallowed up of life.”

The idea is that death will strip off the old clothing of this perishable body, but in the resurrection, we will be clothed with a new, imperishable body. So death is depicted as a sort of undressing of the soul from its current garment, with the expectation of putting on a better garment later.

This metaphor emphasizes the temporary nature of being “naked” (without a body) between death and resurrection, and the desire to be re-clothed. It’s quite an elegant way to describe the intermediate state and the hope of resurrection.

These symbols and metaphors enrich our understanding by approaching the concept of death from different angles. They speak to our imagination and emotions:

- We feel the dark valley but take courage that God’s light is with us.

- We consider Jesus drinking the cup of death for us, and giving us instead the cup of salvation (Psalm 116:13).

- We see the cross not just as a tool of execution, but as a daily symbol of choosing God’s will over our own.

- We learn that sometimes something must die (like a seed) for greater life to come.

- We rejoice that the bee’s sting is gone from death, thanks to Christ.

- We endure present pains as birth pangs of a new creation.

- And we look forward to taking off this mortal garment and putting on immortality.

All of these metaphors ultimately point to the same truth: for those who belong to God, death is not an ultimate defeat, but a transition under the sovereignty of God.

It can be viewed through many lenses – as sleep, as a valley, as sowing a seed, as removing old clothes – but in every case, it is something that leads to a new morning, a harvest, a new outfit, a new birth.

This deeply biblical viewpoint reframes what would otherwise be an unbearable concept and infuses it with hope and meaning.

Patterns and Theological Threads: From Death Entered to Death Defeated

Stepping back, we can observe a consistent pattern running through Scripture regarding death. It’s an arc that starts with life, dips with the entrance of death, and then rises to the triumph of life over death.

Recognizing this thread helps us see how unified the Bible is on this subject, despite being written over many centuries.

Creation and Life:

The Bible begins with God creating life. In Genesis 1-2, everything God made was “very good” and alive. God breathed life into Adam (Gen. 2:7).

There was the Tree of Life accessible to humans. Death was not part of God’s original “very good” creation. This is foundational: death is an intruder, not the way things are meant to be.

Romans 5:12 confirms this, saying death came through sin. So we see the pattern: first there was life without death.

The Entrance of Death (The Fall):

Next, death enters the storyline as a direct result of disobedience. God’s warning to Adam was clear – death would follow sin. The serpent’s lie, “Ye shall not surely die,” was directly aimed at making them doubt the reality of that consequence.

But when Adam and Eve fell, death indeed took root. They experienced immediate spiritual death (hid from God, felt shame, lost innocence) and began the journey toward physical death (Adam lived 930 years, then died – Gen. 5:5 – so eventually the promise was fulfilled).

Thus, death becomes humanity’s lot.

“In Adam all die,” as 1 Cor. 15:22 states. A pattern we see from Genesis onward is the link between sin and death – they are intertwined twins. “The wages of sin is death” (Rom. 6:23) becomes almost a theme statement for the human condition in the Old Testament.

Virtually every story of tragedy, violence, or betrayal in the OT (and there are many) ultimately underscores this: sin brings suffering and death. This truth is hammered home through the history of Israel (when they obey they prosper, when they rebel they often experience war, famine, plague – all forms of death).

God’s Promise and the Beginning of Hope:

But alongside the entrance of death, God gives a glimmer of hope immediately in Genesis 3:15 – often called the Protoevangelium (first gospel). God tells the serpent that the seed of the woman would one day bruise (crush) the serpent’s head, even though the serpent would bruise His heel.

This is understood as the first prophecy of a Savior who would be wounded (the cross) but ultimately victorious (crushing Satan). In other words, right as death enters, God hints at a Redeemer who will defeat the source of death (Satan and sin).

From then on, the Old Testament is marked by promises and covenants pointing toward life restored: God calls Abraham and promises that through his offspring all nations will be blessed (Gen. 12:3) – ultimately a promise of the life-giving Messiah.

Moses, through the law, shows the people the path of life (“I have set before you life and death… choose life,” Deut. 30:19) – though Israel often fails.

The sacrificial system, as we saw, provides temporary atonement, hinting at a greater sacrifice. The prophets begin speaking more explicitly of rescue from death (like Isaiah’s “He will swallow up death in victory” and Ezekiel’s dry bones vision).

Foreshadowings of Resurrection and Victory:

We’ve touched on stories like Isaac, Jonah (who spending three days in the fish’s belly foreshadows Jesus’ three days in the tomb, as Jesus Himself pointed out in Matthew 12:40), and others that act out a pattern of “death” and “resurrection” in miniature.

Each of those is setting a type that will be fulfilled in Christ. The pattern becomes clearer: sacrifice then deliverance, suffering then glory.

Psalm 22 is a vivid prophecy that starts with agony (“My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” – words Jesus quoted on the cross) and ends with triumph and global praise.

Isaiah 53, likewise, has the servant suffer and die (“cut off out of the land of the living”) but then “prolong his days” and be victorious, implying resurrection. So the Old Testament, while under the shadow of death, increasingly shines light on the hope of life.

Christ’s Fulfillment:

When Jesus comes, He fulfills all the foreshadowings and prophecies. He is the seed of the woman who crushes the serpent’s head (1 John 3:8: “the Son of God was manifested, that he might destroy the works of the devil”).

He is the descendant of Abraham who brings blessing (eternal life) to all nations, and the greater Moses who gives the words of eternal life. He’s the true Passover Lamb whose blood saves us from God’s judgment.

He’s the ultimate sacrifice to which all OT sacrifices pointed – once for all, paying for sin. On the cross He cried, “It is finished,” meaning the debt of sin was paid in full.

This dealt with the cause of death (sin), and by removing sin’s guilt for those who trust in Him, He also broke death’s legal claim on them. Then by rising, He inaugurated the new creation.

In a way, Christ’s resurrection is the start of God’s new world – He’s the first man of the new creation, with a glorified body.

The Bible even calls Him the “last Adam” (1 Cor. 15:45) – head of a new humanity that will live forever.

The pattern of Adam bringing death and Christ bringing life is explicitly laid out: “For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.” (1 Cor. 15:22). Christ reverses the pattern introduced by Adam.

The Church Age – Life in the Midst of Death:

Now we live in the in-between time where Christ has won the victory, but we still await the final removal of death. Believers are spiritually alive (regenerated), yet our bodies still die. We have the promise of resurrection, but we still attend funerals.

The New Testament describes this tension: already we have eternal life, already death’s sting is removed, yet not yet do we see death abolished.

- Paul describes it personally in 2 Corinthians 4:16: “though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day.”

- And Romans 8:10, “the body is dead because of sin; but the Spirit is life because of righteousness.”

So there’s a pattern of inner resurrection life now, with outer resurrection life later. During this age, the gospel is preached to rescue people from spiritual death.

Whenever someone turns to Christ, it’s like a little defeat of death – they pass from death to life (John 5:24).

The church’s mission is essentially a life-saving mission, delivering people from the second death through the message of Jesus. We’re like ambassadors saying, “Be reconciled to God, receive life!”

The Consummation – Death’s Final Defeat:

The pattern concludes in Revelation, where all things are consummated. There is a final judgment where death and Hades give up all the dead (Rev. 20:13) – everyone is resurrected, some to eternal life with God, others to judgment (as Jesus also taught in John 5:28-29).

Then, “Death and Hades were cast into the lake of fire” (Rev. 20:14). It’s a striking image: death itself is thrown away like something to be destroyed.

In Revelation 21-22, as mentioned, we see “no more death” in the New Jerusalem. And interestingly, the Tree of Life reappears in the heavenly city (Rev. 22:2), yielding fruit every month, and its leaves are for healing.

What was lost in Eden (access to the Tree of Life) is restored and even surpassed. The last chapters of the Bible thus mirror the first – but with the story resolved.

The Bible starts with no death, then death tragically arrives; it ends with death eternally removed. This is the grand narrative of Scripture: creation → fall (death) → redemption (cross) → new creation (no death).

God’s purpose is not just to forgive sins in a legal sense, but to completely undo the damage of sin – including abolishing death and all its grief.

One could say the whole Bible is about how God turns death into life. Consider these patterns and parallels that thread through:

- Adam vs. Christ: Adam’s act brought death to all; Christ’s act (dying and rising) brings life to all who are in Him.

- Law vs. Grace: The law by itself resulted in condemnation and death for sinners; grace and truth through Christ result in justification and life.

- Saturday vs. Sunday: Jesus died and lay in the tomb (a silence of death, like the Sabbath rest), but on Sunday He rose (a new week, new creation).

- Bondage vs. Exodus: Israel’s exodus from Egypt involved the death of the Passover lamb and the death of Egypt’s firstborn, but it brought freedom – a metaphorical resurrection for Israel as a nation. Jesus accomplished an exodus for us (Luke 9:31 actually calls His death an “exodus” in Greek) – freeing us from sin and death.

- Seed of the woman vs. seed of the serpent: This long conflict (Genesis 3:15) runs through scripture, with death often seeming to win (as evil often kills the righteous, e.g., Abel, prophets, etc.), but ultimately the seed of the woman (Christ) wins by sacrificing Himself and thereby crushing the serpent. The Revelation imagery of the dragon being defeated and thrown down echoes this final victory over the devil, who introduced death.

In theological terms, Death is the “last enemy” (1 Cor. 15:26) that Christ will destroy. It’s the final echo of the fall that needs silencing. We live with that echo now, but as Christians we know it will fade.

The pattern assures us that God has been working through all history to remove the curse of death. It was not instantaneous; He unfolded the plan over millennia – a plan centering on the death and resurrection of His Son.

It’s also worth noting a pattern in individual Christian experience: dying to self leads to true life. Jesus said, “He that loseth his life for my sake shall find it” (Matthew 10:39).

We often go through personal “death-like” trials (2 Cor. 4:11: “we which live are alway delivered unto death for Jesus’ sake”) but those end up resulting in life (in us or others).

Many testimonies could be seen through that lens: someone “hits bottom” (a kind of death to pride or self-sufficiency), then finds Christ and is raised up a new person. It’s the pattern of the cross applied to daily life.

In sum, the theological thread is this: Death came to all through Adam, but life comes to all who are in Christ. Death and life are major themes that tie the whole Bible together, showcasing God’s redemptive love.

As dark a reality as death is, it is bracketed by the greater reality of God’s eternal purpose to give abundant life (John 10:10).

The narrative from Genesis to Revelation can be seen as God undoing what Adam did – or as one author put it: “Paradise Lost” to “Paradise Regained.” The last pages of Scripture exult that “there shall be no more curse” (Rev. 22:3).

And when the curse of sin is gone, death goes with it, for death is part of the curse. This is deeply encouraging: the long saga with death will come to a glorious end, and unending life with God will be our forever story.

Christ Foreshadowed: Types and Prophecies of Death and Resurrection

A fascinating aspect of Bible study is seeing how many Old Testament people, events, and rituals foreshadow Christ, especially in relation to His death and resurrection. We’ve touched on a few already, but let’s gather some of the major “types of Christ” and prophetic signs tied to the theme of death and victory over it:

Isaac – The Willing Sacrifice:

In Genesis 22, as mentioned, Isaac carrying the wood up Moriah, being bound on the altar, and potentially being sacrificed by his father Abraham is a clear type of Christ’s sacrifice. Isaac was a promised son, miraculously born (Sarah was barren and aged, just as Jesus was born miraculously of a virgin).

He willingly laid down (the text implies no resistance from Isaac). And on the third day of their journey, he was effectively given back to Abraham. The location, Moriah, is in the region of Jerusalem – by tradition, the very mountain could be where the Temple later stood or near Calvary.

Abraham even told Isaac, “God will provide himself a lamb” (Gen. 22:8), and indeed God provided a ram caught in a thicket as a substitute. That phrase and event hint that God will provide the ultimate Lamb (Jesus) to die in our place.

Hebrews 11:19 explicitly sees this as a figurative resurrection – Abraham figured that God could raise Isaac, and he received him back as a symbol. So Isaac’s “death and return” prefigures Jesus’ death and resurrection, and Abraham (a father) offering his son mirrors what it cost the Father in heaven to give His only Son for us.

The Passover Lamb:

On the night of the Exodus, an unblemished lamb’s death meant life for Israel’s firstborn. This is an unmistakable type of Christ. Paul says, “Christ our Passover is sacrificed for us” (1 Cor. 5:7).

Just as that lamb’s blood shielded people from death, Jesus’ blood shields us from spiritual death and God’s judgment.

Notably, the Passover lamb’s bones were not to be broken (Exodus 12:46), and indeed when Jesus died, they did not break His legs (unlike the two crucified with Him), fulfilling that detail (John 19:33, 36).

The Passover feast, kept annually, was a continual pointer to the need for a sacrificial death to bring deliverance.

When Jesus came, John the Baptist announced Him with, “Behold the Lamb of God, which taketh away the sin of the world” (John 1:29). That imagery would call to mind all those lambs slain through Israel’s history and especially the Passover lamb.

The Levitical Sacrifices and Rituals:

The whole sacrificial system, including the Day of Atonement rituals (Leviticus 16), foreshadows Christ’s work.

On the Day of Atonement, one goat was killed (and its blood brought into the Holy of Holies to atone) and another goat (the scapegoat) had the sins symbolically placed on it and was sent away alive into the wilderness, symbolically carrying away the sins.

Jesus fulfills both pictures: He died to atone for our sins, and in doing so He carried them away (as Psalm 103:12 says, “as far as the east is from the west”).

Also, the high priest on that day could only enter the veil with blood – Hebrews draws the parallel that Christ as our High Priest entered the heavenly sanctuary by means of His own blood (Heb. 9:11-12).

Additionally, the firstfruits offering (Lev. 23:10-11) – a sheaf of the first grain harvested, offered the day after the Sabbath following Passover – coincides with the day of Jesus’ resurrection (which was the day after the Sabbath).

Paul calling Jesus the “firstfruits” of the dead (1 Cor. 15:20) ties directly to that ritual.

Jonah – Three Days in the Deep:

Jonah’s story is one Jesus Himself gave as a sign of His mission. Jonah was swallowed by a great fish and spent three days and three nights in its belly (Jonah 1:17).

He describes it as being in “the belly of hell (Sheol)” (Jonah 2:2) and says “the earth with her bars was about me for ever” (2:6) – imagery of being entombed. Then God delivered him and the fish vomited Jonah out onto land, essentially a man brought back from death.

Jesus in Matthew 12:40 said, “For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale’s belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.”

Jonah’s “resurrection” was a sign pointing to Jesus’ actual resurrection. Interestingly, Jonah’s ordeal came about because he sacrificially told the sailors to throw him overboard to save them from the storm (Jonah 1:12).

In a way, Jonah offered himself to death to save others, and then was brought back – another parallel with Jesus.

Joseph – From the Pit to the Throne:

Joseph, one of the sons of Jacob, though not an explicit prophecy, is often seen as a type of Christ in many ways. He was the beloved son of his father, given a special robe (like Christ the beloved Son of the Father).

His brothers rejected him and threw him into a pit (literally a cistern) and then sold him for pieces of silver (Christ was betrayed for 30 pieces of silver). Joseph effectively “died” to his old life when taken to Egypt (Jacob even thought Joseph was dead, based on the bloodied coat).

But years later, Joseph rises to become second in command in Egypt, and through him many lives are saved (from the famine).

When he finally reveals himself to his brothers, it’s almost like he came back from the dead to them – they even were speechless and fearful at first, just as the disciples were frightened when Jesus appeared after His resurrection.

Joseph forgave those who wronged him, saying God used it for good to save many people (Gen. 50:20) – echoing how Christ’s death, though orchestrated by evil men, was used by God for the salvation of many.

So Joseph’s arc from suffering to glory, from figurative death to exaltation, foreshadows Jesus’ trajectory (as well as providing a lesson in God’s redemption of suffering).

Moses Lifting the Bronze Serpent:

In Numbers 21, when Israel was plagued by venomous serpents, God instructed Moses to make a bronze serpent and lift it on a pole; those who looked at it would be healed from the deadly bite.

Jesus directly compares this to His crucifixion: “As Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: that whosoever believeth in Him should not perish, but have eternal life” (John 3:14-15).

It’s a fascinating type because the bronze serpent represented the curse (a serpent, like the ones causing death, made out of bronze which can symbolize judgment).

Jesus was made “to be sin for us” (2 Cor. 5:21) – He took the curse on Himself – and was lifted up on the cross. Those who look to Him in faith are cured from the fatal bite of sin (which would cause the second death).

So even an odd story like that in Numbers was a sneak preview of how God would deal with the fatal problem of sin and death through Christ.

Prophecies of the Suffering Messiah:

We cannot overlook the direct prophecies. Psalm 22, written centuries before Christ, describes crucifixion-like sufferings (hands and feet pierced, bones out of joint, people casting lots for his clothing) and also hints at resurrection (God answering him, and the psalm ending in praise).

Isaiah 53 (around 700 BC) is amazingly detailed – it speaks of one who “poured out his soul unto death,” who is with the wicked in his death (Jesus died between two thieves), who bore the sin of many, yet also “shall see his seed” and “prolong his days” after making his soul an offering (implying life after death).

It even says “by His stripes we are healed” – showing His suffering brings us healing (from sin and its consequences). These prophecies gave Jews the concept of a suffering messiah, although many didn’t fully grasp it at the time (even Jesus’ own disciples were confused by the idea of Him suffering and dying).

But after the resurrection, the early church constantly referred to these prophecies to explain that the Messiah had to suffer these things and then enter His glory (see Luke 24:25-27, where the risen Jesus walks through the OT prophecies for the two on the Emmaus road).

Types of Resurrection in the Prophets:

Certain miracles by prophets, like the resurrections by Elijah and Elisha, can be seen as types of Christ’s resurrection power.

When Elisha raised the Shunammite’s son, the child sneezed seven times and opened his eyes (2 Kings 4:35) – a small detail, but one that underscores it was a real restoration to life.

Elisha’s bones reviving a man (2 Kings 13:21) could be seen as symbolizing that there was life-giving power in God’s holy servant even after death – how much more in Jesus who did not see corruption at all! And of course, Jonah’s story as a prophetic type we already covered.

Feasts and Rituals Fulfilled:

The feast of Firstfruits corresponds to Jesus’ resurrection, as noted. The feast of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement) corresponds to His atoning death.

The Year of Jubilee (every 50th year debts forgiven, slaves freed) parallels the gospel’s proclamation of liberty and release (Jesus in Luke 4:19 applied Isaiah 61:1-2, which alludes to Jubilee, to His ministry).

While Jubilee is not directly about death, it is about deliverance from the bondage that often led to death (debt slavery, etc.) – metaphorically linking to how Christ’s work releases us from bondage to sin and death.

To the careful student, these types and prophecies build faith that Jesus’ death and resurrection were not random events, but the grand fulfillment of a plan God had been hinting at all along.

It’s as if God left breadcrumbs throughout history – in the lives of the patriarchs, in Israel’s ceremonies, in prophetic visions – all leading to the cross and the empty tomb. This not only validates Jesus as the true Messiah, but it shows the coherence of God’s Word.

For instance, when Jesus said “Abraham rejoiced to see my day: and he saw it, and was glad” (John 8:56), one interpretation is that Abraham saw a preview of Christ’s work in the offering of Isaac or perhaps in other revelations, and was glad that God would one day deal with death and provide salvation.

- After Jesus rose, the Bible says He opened the disciples’ minds to understand the Scriptures, that “thus it is written, and thus it behoved Christ to suffer, and to rise from the dead the third day” (Luke 24:46).

We aren’t told exactly which Scriptures He went through, but likely many of the ones we just discussed (and more). What a Bible study that must have been!

One more subtle type: The story of Ruth and Boaz – Boaz as a kinsman-redeemer who marries Ruth and raises up offspring, preserving the family line (which leads to King David and ultimately Jesus).

While it’s more about redemption than death, it occurs against a backdrop of death (Naomi’s husband and sons died, leaving the women destitute). Boaz’s act of redemption brings life back to Naomi’s family.

Though not directly a resurrection, it symbolically turned the “death” of that family line into new life (Obed, their son).

The genealogy at the end of Ruth connects to David, and ultimately Christ, who is the ultimate kinsman-redeemer who had to die to redeem us, His bride (the church), and gives us new life and a family name.

All these types and prophecies converge on Jesus. Seeing them enhances our appreciation that God had a master plan to defeat death from the very beginning.

Jesus is the Lamb “slain from the foundation of the world” (Revelation 13:8) – meaning in God’s foreknowledge, the sacrifice was as good as done even from creation’s start. That’s why hints of it are embedded in early Genesis and throughout.

Understanding these connections strengthens our faith and also adds layers of meaning when we read the Old Testament.

For example, the next time you read of the ram caught in the thicket for Isaac, you might picture the “Lamb of God” with a crown of thorns (thicket around His head) provided in our place.

Or when you celebrate the Lord’s Supper (Communion), which Jesus instituted at Passover, you can recall the original Passover night and see how Jesus reframed that meal around His own death (“This is my body… this is my blood” – Luke 22:19-20). It’s all woven together.

Conclusion: Living in the Light of Christ’s Victory Over Death